The arguments against human drivers are irrefutable. We get distracted, we are impatient, our reflexes are limited, we tire out, we talk too much. I agree 100%.

Yet I am always perplexed at the standard talking point for automation in ground mobility. Over a period, some of the presenters in a conference would straddle a familiar rationale. It goes like this. First, US consistently has annual road fatality of over 40,000. (True, and scary). Second, 94% of these events found human error as the root cause, implicitly referring to a 2015 NHTSA memo. Third, therefore getting the human operator out of the equation is the best thing for overall road safety.

More this argument became popular, more I wondered if we have collectively re-framed a potential ‘Contribution Factor’ as ‘Causation’! What about slippery roads, dark nights, rain, hail or snow, over-crowding or a number of other known or unknown environmental factors that could have played a part and could have challenged even the smartest robot, envisioned by Isaac Asimov? Don’t get me wrong. I am not suddenly trying to be the proverbial luddite. I am excited to see the progress in automation, sensing and assist systems in vehicles since the first DARPA challenge in 2004. In fact, one could argue that the history of human civilization is partly a story of continued automation in every area of technology. But today, I just want to turn the standard talking point around a bit.

First, the NHTSA memo did not appear to qualify the human action or in-action as the sole root cause, but that the driver was the last event in the causal chain leading to the event.

Second, even if we assume that getting the driver out indeed is the panacea, we need to remember that the bar set by the human driving is actually not that low. Currently in the US, road vehicles average an annual fatality of 1.34 for 100 million miles of driving (1.00 per 74 million miles), according to IIHS or Insurance Institute of Highway Safety. Now the point is not to under-emphasize this number, because every single road fatality is one too many. The point is that this gives a reference or minimum requirement for an automated system to at least match, and potentially to far exceed.

Third, with a bit more training for certain special group of operators, such as school bus drivers, this number is even higher by a factor of 6. According to National Safety Council (NSC) 2018-19 data[i], average annual national fatality related to a school bus accident is about 120. With an average of 480,000 yellow school buses logging 12,000 vehicle miles travelled (VMT) annually, this translates to a fatality of 1.00 per 480 million miles.

Road Safety & Human Operator

Are you really ready to ‘get the operator out’? What is important – to get the human operator out or improve road safety in all ways possible? Road safety has many facets and contribution players. While the industry can continue to perfect more automated vehicles, let’s focus on all these facets, e.g., a broad and universal deployment of passive/active safety systems combined with state-of-the-art ADAS solutions and smart traffic systems show all the promise of significantly reducing crash and fatality right now. Let’s continue to make the journey without resorting to a poorly framed logic of 94% human error.

Let’s look for insights from aviation. In spite of its early start and relatively deterministic operational design domain (ODD) of most of the flight path, aviation systems are yet to be fully (i.e., 100%) autonomous and requires someone to be at the helm. As my colleague Alaa Khamis and I recently discussed at an IEEE conference on Smart Mobility[ii], both auto-pilot, fly-by-wire technologies, combined with situational awareness and engagement of the pilot continue to play an important role in operational safety of the aircraft. There are many recent examples when the absence of timely intervention during rare moments of unforeseen flying conditions or system failures led to catastrophic results, as in the 2014 Air Algerie flight 5017, where faulty data on de-icing let the autopilot make incorrect adjustments leading to an irreversible loss of control. Similar circumstances seem to be behind several recent aviation events. On the other hand, there are also examples of situations where, agile, aware, and well-trained pilots have rescued planes from unforeseen malfunctions, fly-by-wire glitches or unexpected weather events, as in the 2009 un-powered emergency landing of the US Airways Flight 1549 piloted by now famous Captain Chelsey B. “Sully” Sullenberger.

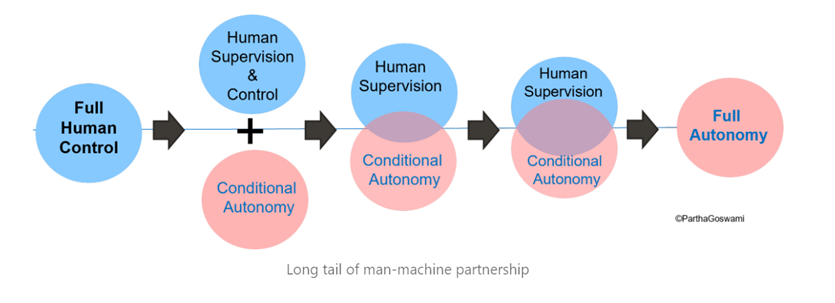

Extending the same rationale to automotive applications, it is perhaps reasonable to say that until the autonomous systems are intelligent enough to handle rare/unpredictable situations, the human operator can play a critical beneficial role by staying in the loop and combining his/her situational awareness and skill with the machine for best operational safety of the system.

References:

[i] NSC Injury facts – https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/motor-vehicle/road-users/school-bus/

[ii] Automated Mobility: A Comparison between Aviation and Automotive, Alaa Khamis & Partha Goswami, IEEE International Conference on Smart Mobility, March 2023

Disclaimer: The comments, thoughts and opinions described are purely author’s own and do not represent the position of either his employer or anyone else.